Have you ever stopped to think that you might have walked through a sacred place without knowing it?

The true journey along the Inca Trail doesn’t begin at a point on the map, but with a much deeper question: Why? What motivated an empire to dedicate entire generations to building a network of roads that crosses jungles, deserts, and imposing mountains? This is a story written in stone, preserved for more than five centuries, and it can transform your next trip into a genuine adventure of discovery.

Above 4,000 meters above sea level, in places where the air is thinner and the wind seems to set the pace, a colossal red network of stone paths stretches out: the Qhapaq Ñan. This monumental work is not only a feat of pre-Hispanic engineering, but also irrefutable proof of the high level of political, social, and cultural organization achieved by the Inca Empire.

Throughout this journey, we will delve into the history of the Inca Trail through five key stages, exploring the reasons for its creation and the fundamental role it played in the expansion of the Inca Empire. We will discover how these roads were not simply routes of passage, but the true arteries that gave life to one of the most powerful empires in the Americas.

Opening remarks: Are the Qhapaq Ñan and the Inca Trail the same thing?

The short answer is: not exactly. Although in common parlance both names are often used interchangeably, they actually describe different things. Understanding this difference is key before delving into the history of these ancient roads.

The Qhapaq Ñan, which in Quechua means something like “the great route” or “the main road,” was the immense system of roads that connected the entire Inca Empire. It wasn’t a single road, but a gigantic network exceeding 30,000 kilometers in length, created to connect and organize the territories of Tahuantinsuyo. Its routes crossed what we know today as Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, giving a clear idea of the impressive scale of Inca power.

When we talk about the Inca Trail, however, we are referring to only one of those many sections, although undoubtedly the most famous. This name is primarily used to identify the route connecting Cusco with Machu Picchu, renowned for its extraordinary engineering, the numerous archaeological sites along its length, and its immense symbolic and ceremonial value. In other words, it is a prominent part of the system, but not the entire system.

Furthermore, this was not the only sacred road within the Inca network. The Qhapaq Ñan served not only administrative or military functions but also held profound spiritual significance. Many of its routes led to huacas, sanctuaries, and mountains considered sacred, and were traveled in the context of pilgrimages and ceremonies. Because a large portion of these roads has been lost, altered, or has not yet been thoroughly studied, it is currently impossible to determine how many ritual routes actually existed.

Why are they often confused?

Largely due to tourism marketing and simplification. “Inca Trail” sounds more evocative and accessible than “the ceremonial Cusco–Machu Picchu section of the Qhapaq Ñan.” But as a cultural traveler, you’re already one step ahead.

Chapter 1: The visionary behind the Inca Trail

In the mid-15th century, a visionary Inca ruler—Pachacútec Yupanqui—turned geography into a tool of political, military, and symbolic power. Under his leadership, the empire didn’t just expand; it became a unified organism.

During this period of imperial reorganization, an exceptional route was created—one not intended for trade or the movement of armies, but for ceremonial use: the access road to the sanctuary of Machu Picchu.

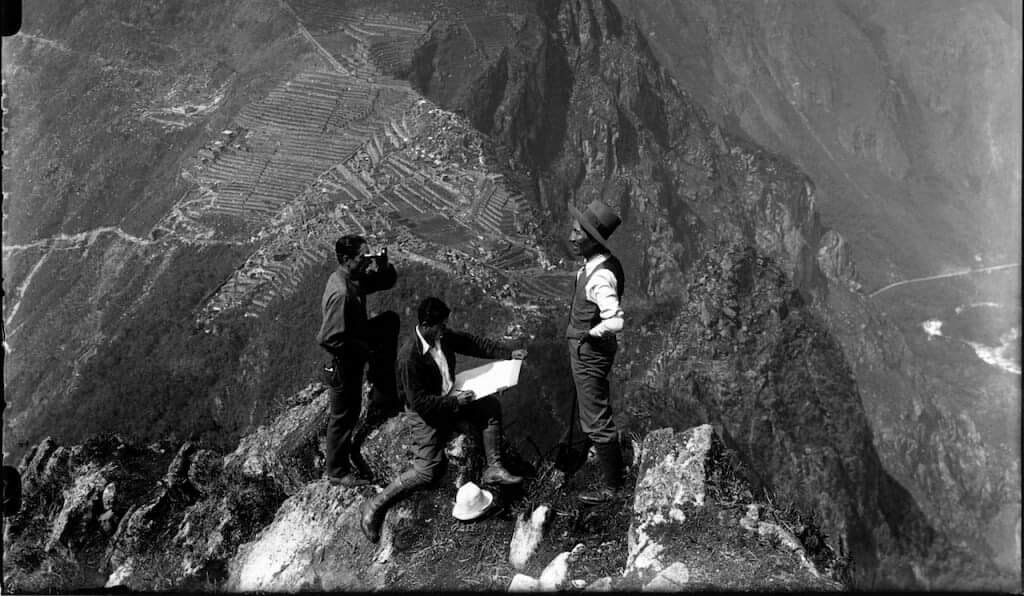

This was no ordinary road. While archaeologist John Hyslop famously compared the Inca road system to a “permanent military operation,” the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu represented its most symbolic and ritual dimension—a project reserved for the elite, where engineering served spirituality.

The men who moved mountains: Who built it?

The answer challenges a persistent myth: they were not slaves. Inca society did not function that way. The key was the mita system, a sophisticated form of rotating labor tribute that was both a duty and an honor for conquered communities.

The true specialists were the mitmaqkuna (or mitimaes): groups of entire families strategically relocated throughout the empire. They were not unskilled laborers, but artisans, stonemasons, planners, and experts in local landscapes who brought their knowledge to new projects. Imagine a coastal water-channel expert being relocated to the Andes to design the perfect drainage system for a new section of road. That was the Tawantinsuyu in action—a massive redistribution of human talent in service of an imperial vision.

A window in time: When was the trail built?

Mark your timeline between 1440 and 1530 AD—this was the golden century of large-scale construction. More specifically, during and after the reign of Pachacútec (1438–1471) and his successor Túpac Yupanqui (1471–1493).

This was not a project completed in a decade. It was an ongoing process of expansion, improvement, and maintenance that lasted nearly a hundred years, paralleling the empire’s explosive growth. Each new conquest, each new territory incorporated into the Tawantinsuyu, required extending the stone arm of the Qhapaq Ñan to integrate and control it.

Chapter 2: The triple purpose of the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu

The Inca Trail leading to Machu Picchu served a different purpose than the rest of the Qhapaq Ñan. While the imperial road system was designed to unite and govern vast territories, this specific route fulfilled distinct functions.

Its existence can be explained through three main purposes.

1. Spiritual purpose: A ceremonial route to the sanctuary

The Inca Trail functioned as a ritual pilgrimage route, primarily intended for priests and members of the Inca elite. It led to the sanctuary of Machu Picchu and to Inti Punku, a highly symbolic space associated with the worship of the Sun god.

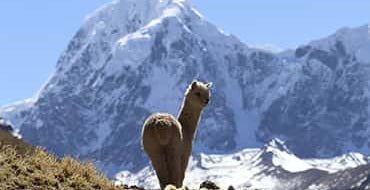

Traveling this path was itself a ritual process. Andean cosmology framed the physical journey through the mountains as a way of approaching the Apus, the sacred mountains. Unlike other sections of the Qhapaq Ñan, here the journey itself held deep symbolic meaning.

2. Political purpose: A display of state power and control

Building the Inca Trail in such extreme geography served a powerful political and symbolic function. Mastery of high mountain passes, carved staircases, and suspended sections demonstrated the Inca State’s ability to dominate the Andean landscape—even in the most inaccessible areas.

This was not a road for mass transit. Royal authorities likely restricted its use to royal envoys, elite messengers, and high-ranking individuals, reinforcing its exclusive character and direct connection to imperial power.

3. Elite logistical purpose: Ceremonial supply

The Inca Trail enabled the controlled transport of prestige goods, ritual offerings, and essential resources required to sustain Machu Picchu and its high-status inhabitants.

Unlike the broader Qhapaq Ñan, which supported the empire’s general logistics, this route fulfilled a specialized logistical role, focused on ceremonial supply rather than trade or regular transportation of goods.

Chapter 3: Archaeological sites along the Inca Trail

Now, let’s turn the names on your itinerary into a personal guide to meaning. Instead of seeing “ruins,” you’ll begin to read the history of the Inca Trail in every stone—following the exact order in which you’ll encounter them on the trek. For detailed descriptions of each site, visit our guide to the archaeological sites along the Inca Trail.

Llactapata: “The first glimpse”

Its Quechua name means “Town on the Heights.” This first major complex was far more than a simple resting place. Its strategic location suggests it functioned as a lookout and control point for access to the valley. In addition, the alignment of some structures with solar events points to a possible use as an astronomical observatory, marking ritual or agricultural cycles for travelers.

Runkurakay: “The stone drum”

A unique circular structure along the trail. Its shape and mid-slope location suggest it served as a tambo, or rest lodge. However, its circular design—unusual for storage facilities—has led archaeologists to believe it may also have had a ritual or ceremonial function, perhaps connected to observing the sacred landscape that surrounds it.

Sayacmarca: “The impregnable citadel”

Its Quechua name translates as “Dominant Town” or “Inaccessible Town.” Built atop a rocky outcrop, this site occupied a strategic and easily defensible position. Its complexity—plazas, enclosures, and water channels—indicates it was more than a fortress; it was a small administrative and religious center that visually controlled the entrance to the cloud forest, regulating the movement of people and goods.

Phuyupatamarca: “The town above the clouds”

In Quechua, the name means exactly that. Perhaps the site with the clearest and most fascinating purpose. Here you’ll find a series of ritual fountains and water channels forming stepped baths. This was a purification complex. Elite pilgrims would cleanse themselves physically and spiritually here, high in the mist, before beginning the final descent to the sacred sanctuary of Machu Picchu.

Wiñay Wayna: “Forever young”

The architectural jewel of the trail and a dress rehearsal for Machu Picchu. Its impressive curved terraces are a scaled-down model of elite Inca agriculture. The complex combines a ceremonial sector—with finely crafted structures and fountains—and a residential area, suggesting it was a vital center of production, ritual, and rest for royalty and priests in transit.

Inti Punku: “The final revelation”

This archaeological site takes its Quechua name, meaning “Sun Gate,” from its ceremonial role. Inca builders constructed the portal with remarkable precision and aligned it with the June solstice, when the rising sun illuminates the entrance at dawn. Its purpose was spiritual: to frame and reveal to pilgrims their first and most powerful view of Machu Picchu, transforming their arrival into a moment of profound symbolic and religious significance.

Chapter 4: Abandonment and rediscovery of the Inca Trail

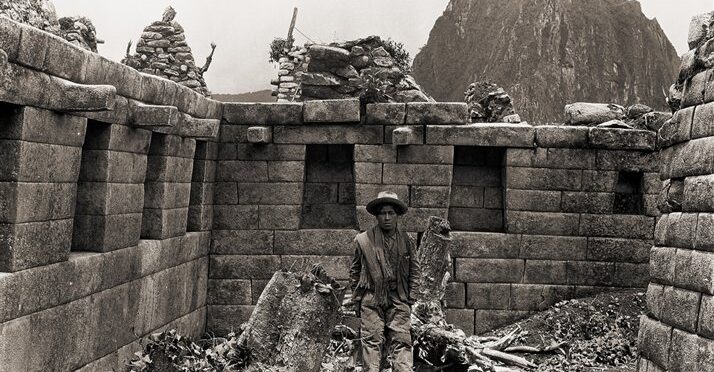

After the fall of the Inca Empire in the 16th century, the cloud forest began a slow and silent task: reclaiming the sacred path. This route, along with the sanctuary it led to, fell into nearly 400 years of obscurity. Yet the story of the Inca Trail, like that of all great works, still had a second act.

The era of forgetting (16th–19th Centuries): Why did the Spaniards never reach Machu Picchu?

After the Spanish conquest (post-1530), the trail completely lost its ceremonial and political role. However, the idea that it remained “entirely hidden” until 1911 is a powerful myth.

Evidence suggests that the history of the Inca Trail and Machu Picchu is far more complex—and far more fascinating:

The true “discoverers” were always the local communities. The Quechua families living in the region—whom American explorer Hiram Bingham encountered—had always known of Machu Picchu (“Machu Pikchu” in Quechua, meaning “Old Mountain”). For the Andean world, it was never a “lost city,” but part of a living landscape and collective memory.

Why are there no Spanish records?

A well-supported hypothesis—backed by archaeological clues and extensive oral tradition—suggests that Inca resistance groups or local communities deliberately burned sections of the trail and sites such as Llactapata.

Objective: To confuse and discourage the Spaniards, protecting high-altitude sanctuaries and elite refuges during the invasion—such as Vilcabamba, the final stronghold of Inca resistance.

Result: This strategy, combined with the fact that the Inca Trail was a steep ceremonial route (unsuitable for horses or Spanish-style commerce) and led to a sanctuary with no obvious gold, meant that the conquistadors had little incentive to pursue it. Their focus remained on the main valleys.

While the Spanish reorganized the empire from the valleys, local communities continued using sections of the trail for agriculture, herding, and highland connections. People lost their understanding of the route as a unified and sacred corridor leading to Machu Picchu. The trail survived—but its original meaning gradually dissolved into everyday geography.

Chapter 5: From forgotten path to legendary trek

Archaeologists and the Peruvian government restored, studied, and consolidated the route as people walk it today throughout the 20th century. What was once an Inca pilgrimage route gradually became one of the most famous and sought-after archaeological treks in the world.

World heritage status (1983)

The turning point of this rediscovery came in 1983, when UNESCO declared the Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu a World Heritage Site under a dual designation—both cultural and natural.

What does this mean for the Inca Trail?

It means that people recognized not only Machu Picchu itself, but also the entire surrounding ecosystem—including the specific section of the Inca Trail—as a joint masterpiece of human ingenuity and natural beauty. This designation is the primary international legal instrument protecting the trail from destruction or uncontrolled development, ensuring its preservation for future generations.

Machu Picchu as a world wonder (2007)

The moment that propelled Machu Picchu to global fame came in 2007, when people voted it one of the New Seven Wonders of the Modern World. From that point on, it shifted from a destination for culturally minded travelers to a global tourism icon.

The numbers speak for themselves: annual visits to the sanctuary surged from fewer than 700,000 to more than 1.5 million in just over a decade. This boom made the Inca Trail tickets the most coveted commodity in South American trekking, selling out for the high season more than six months in advance.

Being named a World Wonder didn’t just increase visitor numbers—it transformed the very nature of desire. Hiking the Inca Trail was no longer just an adventure; it became the epic way to arrive at a universal symbol.

Current regulations for conservation

The key mechanism for preservation is a strict, non-negotiable permit system:

- Maximum of 500 people per day: This limit includes hikers, guides, cooks, and porters. In practice, authorities allow only 180–200 tourists to enter each day.

- Booking through AUTHORIZED AGENCIES only: Regulations prohibit independent trekking. You must book through a tour operator licensed by the Peruvian government.

- Permits sell out months in advance: For the high season (June to October), permits typically sell out 6–8 months ahead of time. In the low season, travelers should book at least 3–4 months in advance.

Mandatory annual closure in february

It’s important to note that authorities completely close the Inca Trail throughout the entire month of February, with no exceptions. This annual closure allows for trail maintenance, visitor safety during the rainy season, soil recovery, and rest for the area’s flora and fauna.

We strongly recommend planning your trip well in advance and considering alternative routes during this time. For more details on timing your visit, see our article on the best time to visit Machu Picchu.

Final note: How do we know what we know? A critical look at the sources

The history of the Inca Trail dates back to pre-Columbian times, and because the Inca Empire did not develop an alphabetic writing system, reconstructing that history is like assembling a massive puzzle with many missing pieces.

The three pillars of our understanding

- What the earth preserves: Archaeology provides dates, layouts, and material evidence. It shows us what people built and when, often with remarkable precision. On its own, however, it cannot fully explain motives, meanings, or rituals.

- What the conquerors recorded: Chronicles offer names, accounts of expansion, and descriptions of customs. Yet 16th-century authors wrote these sources in the context of conquest, shaping them with bias, misunderstanding, and political agendas. They do not represent neutral records.

- What scholarship interprets (Ethnohistory): Key researchers such as María Rostworowski (Peru) and John Hyslop (USA) devoted their lives to cross-referencing archaeology with colonial chronicles, filtering out colonial bias to propose models of how Inca society may have functioned. Their work forms the foundation of modern interpretations.

For this reason, readers should understand every claim in this blog—from the role of Pachacútec to the ceremonial purpose of the trail—as a reasonable hypothesis rather than an unquestionable fact. It reflects the best explanation available today based on existing evidence.

Interesting note: If you’d like to dive deeper into the history of the Inca Trail, the Tawantinsuyu, and Inca culture, we recommend authors such as Guamán Poma de Ayala, María Rostworowski, Pedro Cieza de León, and John Hyslop, among others.

Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of the Inca Trail

The Inca Trail is not merely an ancient pathway; it serves as a profound testament to the craftsmanship and organizational prowess of the Incan civilization. Spanning approximately 26 miles, this historic trail connects the famed city of Machu Picchu to the ancient capital of the Inca Empire, Cusco. Constructed in the 15th century, its creation reflected the Incas’ remarkable ability to adapt their engineering skills to the challenging Andean geography. As a key element of the extensive Incan road system, the Inca Trail facilitated not only the movement of armies and goods but also the spread of culture and religion across vast territories.